[ad_1]

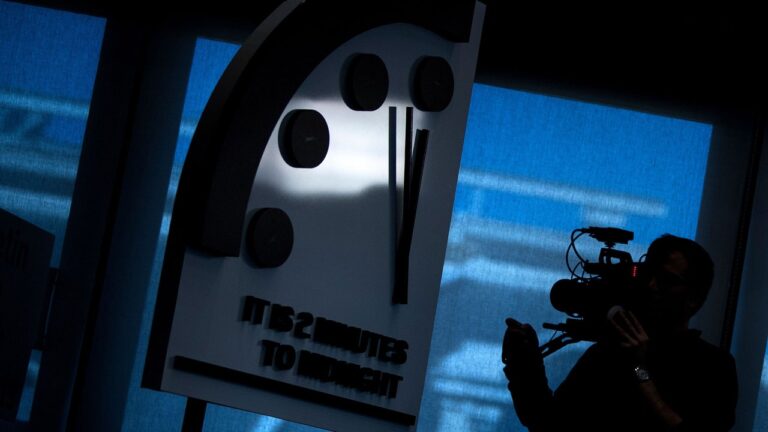

The risk of nuclear disaster tends to shift in more discrete steps. In 1991 the Doomsday Clock stood at 17 minutes to midnight—beyond the original 15-minute scale of the design. It was the furthest from the apocalypse the clock had ever been, thanks to the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty and the disintegration of the Soviet Union. “The setting of the Bulletin Clock reflects our optimism that we are entering a new era,” wrote the Bulletin’s scientists at the time of the announcement.

It’s hard to draw such clear lines with climate change. On one hand, the world is facing a more secure future than if governments had taken no action on climate change. According to Climate Action Tracker, current policies have us on track for around 2.7 degrees Celsius of warming by 2100. This level of warming will have devastating consequences, but it’s better than the situation we were facing in 2013 when existing policies had the world on track for 3.7 degrees of warming. Landmarks like the Paris Agreement and the US Inflation Reduction Act show that meaningful action on climate change is possible.

But at the same time, annual carbon emissions are still rising. While the future is looking better, right now things are still getting worse. This presents a conundrum for the scientists who set the Doomsday Clock. Do they go on future pledges, or the situation right now?

“In my view, and in the view of a lot of us, every year that we continue to emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere the needle should click a little bit forward to doomsday,” says Pierrehumbert. But there’s only so many times you can move the minute hand closer to midnight. Adding more increments would increase the Doomsday Clock’s nuance, but setting the clock at 99.4 seconds to midnight doesn’t exactly have the punch that its original designers were aiming for.

Counting down to midnight is an intuitive way to think about nuclear war. Either the world is at nuclear war, or it’s not. There is nuance here—a tactical nuclear weapon, for example, is not the same as a full-scale nuclear war—but at a very broad level, nuclear war as the original Bulletin scientists thought of it was a fairly binary state of affairs. Climate change is much more nuanced. Most scientists agree that there is no clear cliff edge of disaster when it comes to climate warming. Instead, there is a slow ratcheting of global catastrophes as well as an increased likelihood of climate tipping points, where certain climate systems alter suddenly and irreversibly.

These high-impact, low-probability events are poorly understood, but they’re not the only ways that climate change can have a severe effect on the planet. As existential risk researcher Luke Kemp has noted, a much warmer world is less resilient to other kinds of catastrophic risks. It’s harder to imagine humanity bouncing back from a terrible pandemic or a nuclear war in a world with catastrophic levels of warming. Climate change isn’t only a doomsday risk in itself—it’s a risk multiplier that increases our vulnerability to all kinds of events.

[ad_2]

Source link